On Being Erased

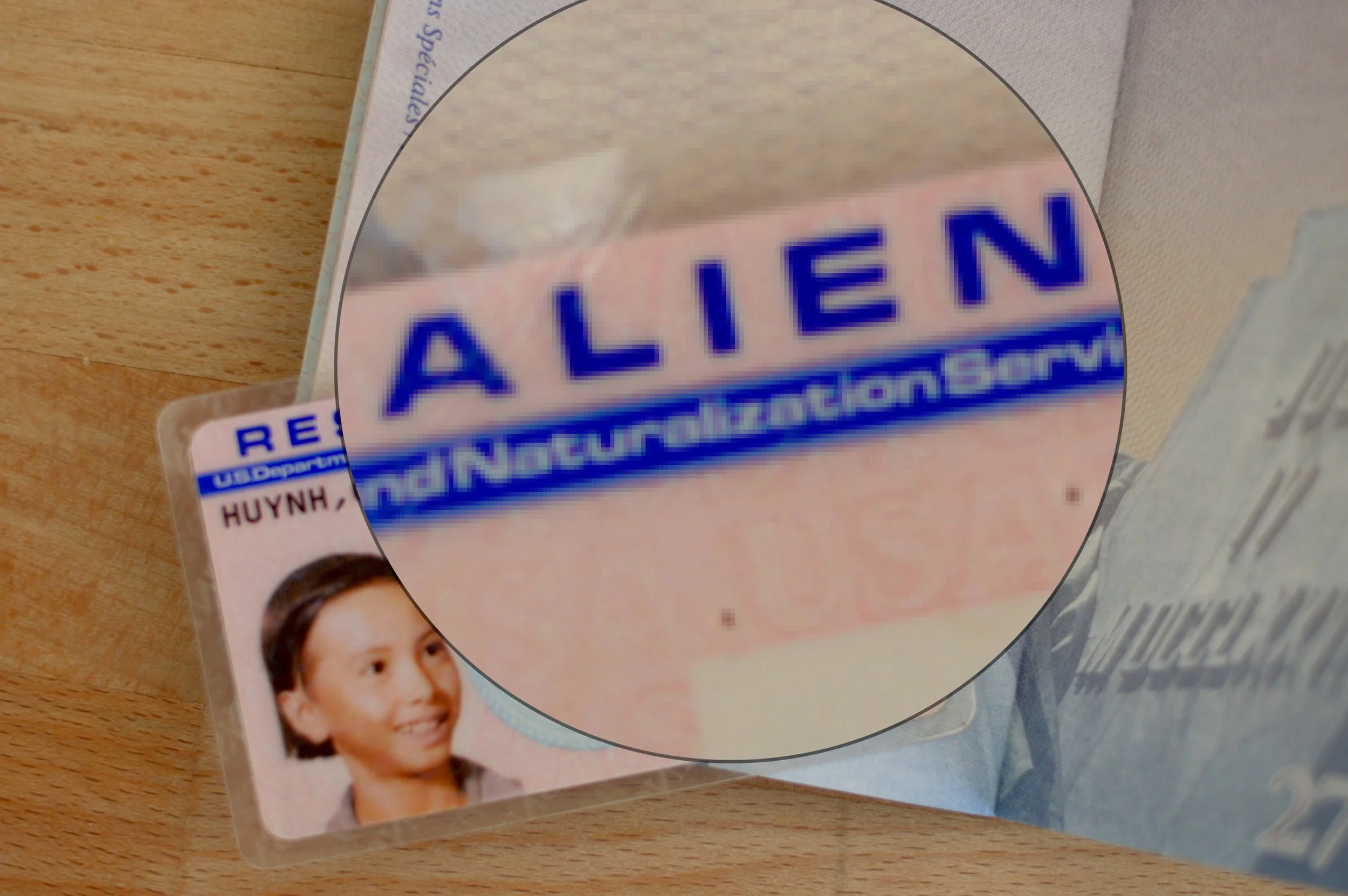

by Que-Lam Huynh

On Being Erased

by Que-Lam Huynh

I was a second-year doctoral student, bright-eyed and star-struck at the biggest conference in our field. You, a white woman, senior faculty member, well-respected as a researcher, mentor, and community activist.

My Chicano colleague and officemate, your former student, introduced us.

There were three of us to be introduced: three Asian American women.

“Wow, just a bunch of Asians in your lab eh? I try not to do that in mine,” you casually said to him with a laugh.

You never made eye contact with us.

I was shocked that someone like you would say something like that in my presence. But I knew exactly what you meant because I’ve heard it a thousand other times.

“You are all alike.”

You, a white woman, senior faculty member, well-respected as a researcher, mentor, and community activist, were assigned to be my mentor when I started my first tenure-track faculty job.

***

At this same academic conference, we were accosted by a frantic white woman.

“How do you pronounce this name?” she asked as she shoved a piece of paper into our faces.

“I don’t know,” my life partner responded.

She was sure we should know.

She said it again with more emphasis, “How do you pronounce this name?? I have to introduce him at the next symposium, and I don’t know how to pronounce his name.”

We both looked blankly at her.

Lady, we are not the people you think we are. We are not the people you’d hoped could help you because of our almond shaped eyes and yellow-brown skin.

But I knew exactly what you meant because I’ve heard it a thousand other times.

“You are all alike.”

***

I learned early on that I have no place in this country. No comfortable home within the walls of academia. In fact, I learned that even school was not safe for a refugee kid like me.

I was 12 years old when my history teacher, a middle-aged white man with missing right thumb, pointed straight at me and said, “I was in The War.”

It was the end of April, and we were talking about the two paragraphs devoted to the Viet Nam War in our history book.

He told us that the Viet soldiers had abandoned their duties, that they had lost the war. That he and his friends had fought long and hard. He even had a missing thumb to show for it. Some of his friends came home in caskets.

I fumed. I’d never talked back to a teacher before, but this time it felt different.

Finally, I raised my hand, “Sir, I also know people who fought in that war, and they said the Americans abandoned us. We didn’t lose that war. You did. Millions of our people died during and after.”

Mr. History Teacher sent me straight to the principal’s office.

“Don’t come back to my class again until you can show some respect.”

You wanted me to respect your lost thumb. I wanted to tell you about my uncle’s missing legs and 1 functioning kidney. I wanted to tell you about another uncle who came home full of shrapnel, fragments of the war left by doctors to work their way out of his body over time.

Most of all, I wanted you to know about my auntie, mom’s youngest sister, who survived 10 days at sea in a tiny little thing we couldn’t even properly call a boat—a thing made for transporting goods through riverways, not people across oceans, huddled together with 107 other people with almost no food or water to speak of, fighting off Thai pirates, until they were rescued by fishermen. My auntie, who spent more than a year at Galang Refugee Camp in Indonesia before she was “accepted” by the “good” people of Australia, the same people who at that time had not yet apologized nor made financial reparations to Aborginal peoples. My auntie, who kept with her a picture of us at the Sai Gon zoo, a picture that survived her harrowing escape from our homeland, one that kept her company when she missed us which was all the fuckin time.

There were so many more things I wanted to tell you, but America has left you without the ears to properly listen to a child who looked like your enemies.

I was shocked that someone like you would say something like that in my presence. But I knew exactly what you meant because I’ve heard it a thousand other times.

“You are all alike.”

***

I was a 16-year-old high school sophomore. You, a black kid twice my size, and your friend, a white kid also twice my size.

“Ching chong!” you said mockingly as I passed you on my way to the school counselor’s office.

“What did you say?!?” I spun around and shouted.

“Ching chang chong!” you repeated, your fists clenched.

I knew better than to fight two boys twice my size. So I walked away, fists also clenched. Utterly disappointed at myself and at you.

I was shocked that someone like you would say something like that in my presence. But I knew exactly what you meant because I’ve heard it a thousand other times.

“You are all alike.”

I never saw you in school again, but your words are etched in my memory.

***

I was in my second year of that tenure-track faculty job. You were more senior than me in rank. We were sitting in the back of the room during a candidate’s teaching demonstration. Me—next to a Chinese American junior faculty member—next to you, a white man.

You were eating a Cup O’ Noodles.

When the candidate was done, you turned to us, Cup O’ Noodles still steaming, to say, “She was good, but we already have too many Asians in the department!”

That other junior faculty member and I, we laughed nervously.

I was shocked that someone like you would say something like that in my presence. But I knew exactly what you meant because I’ve heard it a thousand other times.

“You are all alike.”

I was relieved that you weren’t on the personnel committee when I went up for tenure.

***

When I was 11, my mom and I moved into a working-class, mostly white and Latinx neighborhood in northwest Phoenix, Arizona. Pat—a maid, and Jim—a janitor, next door. Mike—a machinist, on the other side, and Phil—an electrician, two doors down.

Our first weekend in that new house, Jim saw me struggling with an electric mower twice my size in the fro1t lawn. After a few hours, while I worked on the backyard, he jumped over the fence with his gas mower and went to work with me.

Many late nights, while I obsessively practiced my dribble in our driveway, Jim sat in his smoking cigarettes and listening to old-timey country music on a battery-operated radio. Pat knew we didn’t have cable, so she always videotaped Chicago Bulls games for me without me ever asking.

A few years later, a black family moved in down the street. Jim and Pat weren’t happy. Neither were Mike or Phil. I heard a lot of whispering among the white neighbors.

Pat politely told me, “We like you people, but we don’t want them here.”

I was shocked that someone like Pat and Jim would say something like that in my presence. But I knew exactly what Pat meant because I’ve heard it a thousand other times.

“You are all alike.”

This time, Pat also taught me that to be accepted in this country, I had to be one of the good ones. But I knew we weren’t all good.

There was that other Viet family down the street: a couple and their 6 children in a one-bedroom apartment. He was the only one earning a living in the family, his wife and kids on welfare and food stamps. He relentlessly beat them whenever he was home, drunk and angry at the world and anything that got into his way.

Their eldest daughter dropped out of high school after 1 month. I soon learned that she was a teenage mother, impregnated by a Viet boy 4 years her senior, one of my classmates. That boy finished high school with me, but that girl never went back.

If Pat knew about that other Viet family, would she still think of us in the same positive light?

The black family didn’t last more than a few months in our neighborhood. I was too scared to say hi to them or their kids while they were there.

It took me years to unlearn what Pat and Jim taught me about race relations and about the meaning of my ethnicity.

***

In graduate school, my life partner, future mother of my children, a child of Viet refugees, one helluva Viet woman, kept track of all the Viet academic psychologists she found in her research and online readings.

Khanh T. Dinh, UMass Lowell

Huong H. Nguyen, Brandeis University

There were two.

Years later when we joined the academy as tenure-track faculty, we were two more.

Deep down, I knew this meant something big, especially for those Viet refugee kids out there sitting in classrooms where they are rarely if ever represented.

But to most others, especially to those who told us in coded language that we were in surplus in the academy, we weren’t any different than those other yellow-brown skinned folks whose names they couldn’t pronounce.

“You are all alike.”

***

My life partner still keeps track of all the Viet academic psychologists she finds in her research and online readings.

She finds hope and inspiration in this running list.

Maybe our children will have a different educational experience than we did. Maybe they won’t feel so isolated and alone. Maybe they will get professional guidance in whatever they do. Just maybe.

“It’s getting longer!” she explains to me whenever I wonder aloud why she does this.

It doesn’t matter, love. In their eyes, we are all alike.

***

In my psychology class on diversity and equity at a large public university, I ask my students why Asian Americans are so successful?

Hands of all shades fly high in the air: Asians work harder. Asians are good at math. They value education. They have tiger parents. They’re really smart. Asians don’t experience discrimination, not anymore.

“Have you ever heard of the model minority myth?” I ask my excited students.

“No, professor. What is that?”

“What about the history of U.S. immigration policies toward various Asian groups? Have you ever heard about that in any of your classes?”

“No, professor. What do you mean?” Heads are cocked and eyes are wide. They seem ready for what’s coming next.

I take a deep breath. This is my chance to teach a room of young people what America has buried and silenced. This is my way of helping them to connect the dots between the struggles in their own communities and that of my peoples.

This is my way of calling out the racist system that pits us against ourselves and against each other. This is how I build solidarity.

This is my middle finger to all the times I was rendered powerless and speechless by, “You are all alike.”

Que-Lam Huynh resettled with her single mother to the U.S. at age 11 and eventually found a place that felt like “home” in Los Angeles, CA. She currently is a professor of social psychology at California State University, Northridge. Her academic work has been published in peer-reviewed journals such as Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, Psychological Assessment, and Asian American Journal of Psychology. She finds hope and inspiration in teaching and mentoring students, and she strives to be a worthy parent to her amazing children.